16th - 18th Century Black Historical Hidden Figures

Black people have been in Europe for centuries, as musicians, royalty, academics and literaries cementing their place in European history - even if it has been hidden.

We thought it best to spotlight people who have been omitted and obscured in history. Such hidden figures as outlined below, are the men and women who excelled in the onset of the modern world, whose vigour and service enlightened many between the 16th and 18th centuries.

Allessandro de Medici (1510-1537)

Meet Alessandro de Medici, Duke of Penne and Florentine Republic. Despite the plethora of portraits of the beguiling 16th century Italian Renaissance noble, his African heritage is seldom mentioned. Lest we and history forget that he was arguably the first, if not most visible, Black head of state in Europe.

Allessandro de Medici

In 1510, Medici was born to Simonetta da Collavechi, a Black serving woman in the Medici household, in Florence. Though the details of his mother are relatively known, there has been much dispute about his paternity. His paternity is ascribed to either Lorenzo de’ Medici (1492–1519), duke of Urbino, or, to Giulio de’ Medici, nephew of Lorenzo the Magnificent.

What is certain, however, is that Alessandro wielded great power as the first duke of Florence. Alessandro was made the duke of Penna by the Holy Roman emperor Charles V (1522) and was the first Medici to rule Florence as a hereditary duke (1532–37), and the last Medici from the senior line of the family to lead the city.

Asides from being patron of some of the leading artists of the era, he is one of the two Medici princes whose remains are buried in the famous tomb by Michaelangelo.

Francis Williams (1702-1770)

Meet Francis Williams, Jamaican scholar, polyglot, and lyricist of Latin verse. Born to John and Dorothy Williams, free African people in Jamaica, their family was one of few to enjoy the privileges of social and economic liberties. Their status was anomalous.

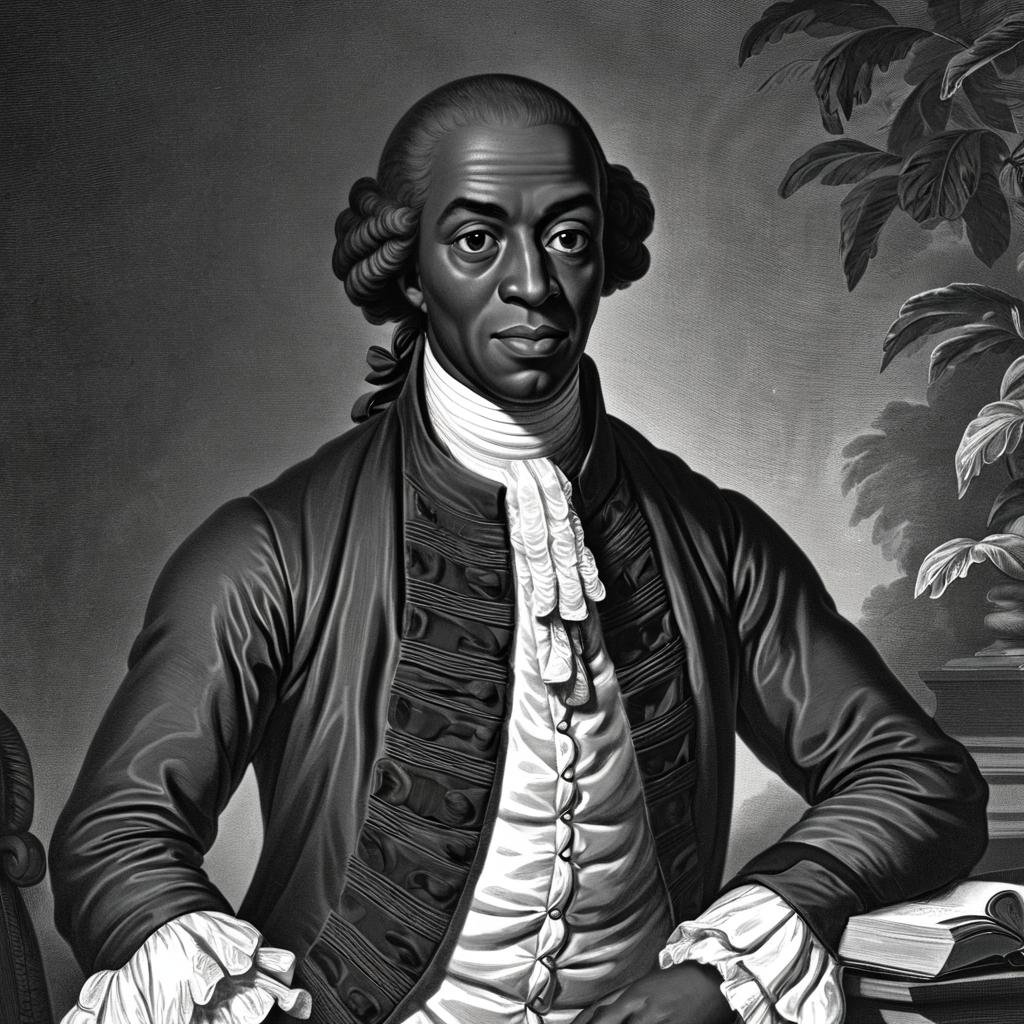

Francis Williams

In 1708, a petition was filed in Jamaica on behalf of John Williams, resulting in him “being granted the rights to the known laws, customs, and privileges of an Englishman.” Thereafter, Williams became the subject of what has been characterised as a social experiment by John, Second Duke of Montagu, then prominent Governor, who sponsored a number of Africans to study in England.

Francis excelled in England and after taking an oath of citizenship in 1723, he obtained degrees in Mathematics, Latin and Literature. Williams is reputed to be the first person of African ancestry to attend and graduate from Cambridge University, despite no record of his attendance has been found. Williams was also a literary extraordinaire – as a poet of Latin verse - his work was critically embraced by some in the literary community in London. He is best remembered for “An Ode to George Haldane”.

Francis Williams returned to Jamaica the following year to take over his father’s business in the wake of his passing. Williams then opened a school in Spanish Town, Jamaica where he taught reading, writing, Latin and mathematics, until his death in 1770 at the age of 68.

A portrait of Williams hangs in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. The portrait features Williams as a scholar in his study and while reflecting the flair of European elite gentlemen of the era, an open window reveals the idylls of Spanish Town, his Jamaican hometown.

Anton Wilhelm Amo (1703-1759)

Meet Anton Wilhelm Amo, the first West African student to study and obtain a doctorate in Philosophy from a European University.

Anton Wilhelm Amo

Historians have long contemplated the circumstances surrounding his emigration to Amsterdam. Some hypothesise that it is likely that he was sponsored by Dutch missionaries to receive a Christian education in Europe while others cite the Dutch West India Company and the slave trade (his brother was enslaved). In either case, Amo found himself sojourning from Ghana, his homeland, to the Dukes August Wilhelm and Ludwig Rudolf von Wolfenbüttel, who embraced him as a member of their kin. It is believed that they provided him with the opportunity to pursue an academic career in philosophy.

Amo was educated at the Wolfenbüttel Ritter-Akademie and at the University of Helmstedt (1721–27). Amo, who knew Dutch, German, French, Latin, Greek and Hebrew, then went on to the University of Halle’s Law School in 1727.

A few years later, he moved to the University of Wittenberg, in Saxony, where he became the first African to earn a doctoral degree in philosophy. There, he wrote a thesis about the legal status of the “Moor” arguing that the European slave trade violated the principles of Roman law. This manuscript on The Rights of Moors in Europe is lost, but a summary was published in his university's Annals (1730). And in 1738 he published an academic text, before lecturing at two eminent institutions of higher learning, in Halle and in Jena. In 2020, Oxford University Press published a translation (into English) of his Latin works from the early 1730s.